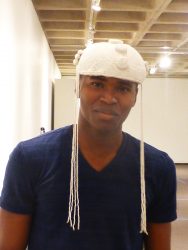

On display in Drake University’s Anderson Gallery, alongside oil lamps, ceremonial bags, an iron healers’ staff, wooden masks, and other artifacts is an intricately designed wig. Its cloth interior is covered in ring after ring of tiny white glass beads, some in the pattern of curls and buns, to simulate the look of a British barrister’s wig.

To Drake student Morayo Adeyoju, the item is more than an obscure artifact from a culture on the other side of the world. “It’s like, a family heritage thing,” says Adeyoju. His grandfather was a king from the Yoruba tribe in Nigeria and wore a very similar headpiece.

“When I was young, I would sometimes put the crown on my head and be like, ‘Bow to me,” Adeyoju remembers with a laugh.

Adeyoju, a senior actuarial science and math double major, lived with his father and grandparents in a palace until he was 15 years old. Visitors were required to bow to his father and grandfather, and due to cultural customs, Adeyoju himself was discouraged from looking his father in the eyes. He shared these cultural practices—and many more—with the Drake community through the exhibit “Apparatus: The Technology of Seeing/Worldviews,” on display in The Anderson Gallery through October 22.

The exhibit also features artifacts, videos, and other exhibits from the Gothic period, Renaissance, 19th century Western nations, early Ming Dynasty, Minimalism, and the USA today—each with its own set of stories. “Apparatus” focuses on exploring the links between technology, culture, and power in seven time periods and places. For the Yoruba people, Metrick-Chen said performance, including associated costumes and movements that are unlike human movement were the technology that linked power to the rest of the cultural apparatus.

Lenore Metrick-Chen, curator of “Apparatus” and associate professor of art history at Drake, emailed the African Students Association in hopes of gathering a student perspective on the section of the exhibit,. She was lucky enough to hear from two Nigerian students, including Adeyoju, who appears in a video that plays on loop in the gallery.

With his father’s side of the family, Adeyoju worshipped Egungun, a spirit who is at the center of the festival featured in the gallery. Adeyoju describes the festival, and other elements of his culture, in a video interview that plays on a loop in the exhibit.

Adeyoju said the one-day Egungun festival occurs in the dry season, which in Nigeria is the months of June, July and August. Each family is trained in an occupation and each family has its own god who has a similar festival. After talking to the gods, a priest picks one male in a family to be the oje, a person who masquerades and dances representing the spirit of the dead.

There is a parade leading to the castle where there is food and dancing. A specific drum, known as a talking drum, invites people to dance.

Visitors to the exhibit will be sure to leave with a different perspective on numerous cultures—including their own. This was true for Adeyoju, who at the age of 15 moved out of the palace to a more urban part of Nigeria with his mother and two half-brothers, who practice Christianity. They moved to Maryland in 2012, and Adeyoju enrolled at the University of Maryland as a pre-medicine student. After deciding to pursue actuarial science instead, Adeyoju found his way to Drake.

“Some of the [artifacts] I’ve seen a lot growing up, but others were all gone during my generation,” he said. “So I was surprised to see them. It was nice to see them, and to be able to share some of my culture.”