Since its humble beginnings in 1904, Drake Stadium has welcomed many champions—men and women who performed extraordinary physical feats.

Carl Lewis, one of the most accomplished track and field athletes in history, helped to shovel snow from his lane on the Stadium’s famous Blue Oval before winning the 100-meter dash at the Drake Relays in 1994.

Michael Johnson won the 200m Special Invitational at the 1996 Drake Relays, just a few months prior to becoming the first athlete to win the gold medal in both the 200m and 400m in the same Olympics.

But from their seats in the Stadium, spectators have borne witness to those athletes who triumphed not only over the competition, but also over adversity—helping to carve out historic advances in racial and gender equality.

A special exhibit opening at Des Moines’ Salisbury House & Gardens in April uses a vast array of memorabilia, archival photos, narrative displays, and trivia games to chronicle the Stadium’s importance for Iowans, and how the Stadium’s story intersects with broader events in history.

“Drake Stadium: Iowa’s Front Row Seat to History” begins with the Stadium’s origin as Haskin Field in 1904—in a “sunken ravine” where 2,500 spectators could sit on concrete benches to watch athletes run the circumference of a dirt track—and carries visitors through present day, when 40,000 fans gather every April to watch hundreds of the finest high school, collegiate, and elite athletes compete in the Drake Relays.

The exhibition runs April 1 through June 6. An opening reception from 6 to 8 p.m. April 1 is free and open to the public; after the opening, the exhibit will be accessible with normal paid admission to the Salisbury House at no extra charge.

“You look at the old [Relays] programs and images, and marvel at the humble beginnings of the Drake Relays, along with the history it has seen,” says Carolyn Hill, assistant director of the Drake Relays.

Humble Beginnings

It took bold vision and dogged perseverance to transform the Stadium of yesteryear to the Stadium of today—a place where athletes help shape the future of sport and the future of the nation.

John L. Griffith, the University’s athletic director, track and field coach, and head football coach from 1908 to 1918, was one such visionary. In 1910 he helped organize the first Relays carnival, which later became known as the Relays. More than 200 athletes competed before an audience of just 100 Drake students for that first event. It was an auspicious beginning, but even then the event showed promise:

“Despite the blizzard that swept across the Drake stadium all afternoon, the first relay carnival ever held in this city was far from being a fizzle,” read an April 24, 1910 article in The Register and Leader. “It was shown conclusively that under favorable weather conditions such a meet would be one of the most successful of the year.”

Carl Weeks, a businessman who made his fortune selling makeup, and his wife Edith settled permanently in Des Moines in the early 1900s. They lived near Drake at 39th St. and Forest Avenue until the 1920s. They commissioned the construction of the Salisbury House, a 42-room Tudor revival home in 1923; the house was finished in 1928 and is now available for public tours throughout the year. Weeks served as a trustee at Drake University for many years. He was instrumental in the formation of the College of Pharmacy, as well as the construction of Drake Stadium.

Vision for the Future

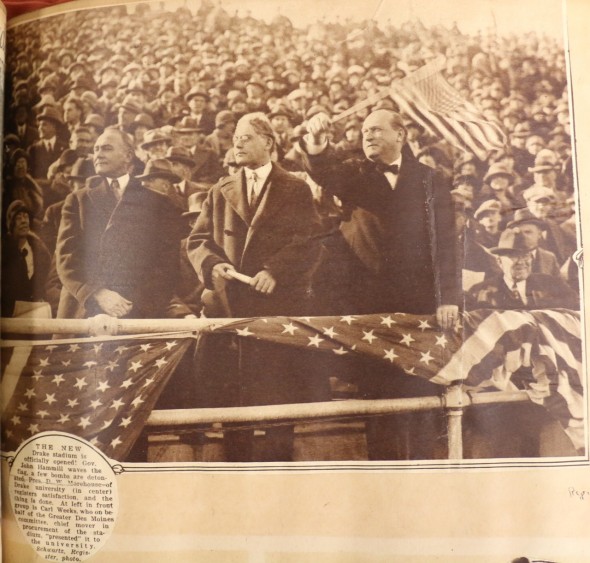

A photo on display in the exhibit shows Weeks alongside Drake’s then-President Daniel W. Morehouse at the opening ceremony for Drake Stadium in 1926. Standing beside them is Mayor Carl Garver, who bears a stoic expression as he waves an American flag. Hundreds of people fill the stands behind them.

It’s as if Weeks, Morehouse, and the others in the photo—originally published by the Register and Leader and retrieved from the University of Iowa’s archives—knew how much history would be made in the Stadium:

- A young Ronald Reagan broadcasted the action of the Drake Relays for WHO Radio, years before becoming 40th president of the United States;

- Jesse Owens, a young athlete from Ohio State University, sharpened his competitive skills at the Drake Relays, where he won the 100-meter sprint and the long jump in 1935, then triumphed over racial adversity when he earned four gold medals at the 1936 Berlin Olympics in Nazi Germany.

- The U.S. Army held civil defense demonstrations on the field in the early 1940s in solidarity with their brothers-in-arms overseas;

- In 1951, Drake’s preseason Heisman candidate Johnny Bright was targeted with a jaw-breaking gridiron hit. Photos of the incident, published by The Des Moines Register and Life magazine, distilled the reality of Jim Crow America;

- Wilma Rudolph raised the bar for female athletes when she won three gold medals at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome. Less than a year later, in April 1961, she arrived at Drake Stadium to run the inaugural women’s race in the Drake Relays; by 1964, the state had formalized high school girls’ track and field, and the first Iowa girls’ state track meet was held at Drake Stadium.

- Jackson Scholz, George Saling, Gwen Torrance, Caitlyn (Bruce) Jenner, and countless other exceptional athletes amazed fans during the Drake Relays.

These moments and others are chronicled in the Salisbury House’s gallery, which incorporates nearly 30 archival images from the Drake University Archives and Special Collections, housed within Cowles Library, as well as the Drake Relays Archives.

The Drake Relays Presented by Hy-Vee demonstrates its continued commitment to excellence during this year’s meet, April 27-30. A schedule of events for alumni and members of the Drake community is also available online.