Imagine you’re a juror in a high-profile murder trial. An expert witness—a forensic scientist—displays a strand of hair found on the body of the deceased; then she compares it with hair from the defendant. The hairs are “microscopically indistinguishable” from one another, she concludes, and it is “highly unlikely” that the two samples came from different individuals.

If this testimony would lead you to believe that the hair evidence strongly suggests the defendant is guilty, you’re not alone. And yet this scenario, during which experts exaggerate the conclusiveness of forensic evidence, forms the foundation for many convictions that have subsequently been overturned through the use of more reliable DNA evidence.

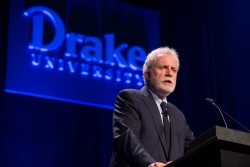

Peter J. Neufeld, founder of The Innocence Project, delved into the roots of wrongful convictions during the 35th Martin Bucksbaum Lecture at Drake University on Oct. 27. His nonprofit organization has used DNA testing to free 333 wrongfully convicted individuals since the group was founded in 1989.

Many of those individuals spent decades in prison before being freed; the average length of time served was 14 years. Meanwhile, the true offenders roamed free—and in 163 cases, The Innocence Project’s work has not only freed the innocent but also helped to identify the real perpetrators.

“We believe these 333 people are the proverbial tip of the iceberg,” Neufeld told the crowd of about 2,000 in the Knapp Center. “In most [criminal] cases there is no biological evidence to test with DNA. So it is incumbent upon us to determine the causes of wrongful convictions and work with researchers to come up with policies and practices that help to reduce these wrongful convictions.”

Neufeld’s lecture, which attracted distinguished guests including several Iowa Supreme Court justices, came at a time when his cause is top-of-mind in the state of Iowa. Two days prior, the Iowa State Public Defender’s office announced that it was forming a special unit to investigate potential wrongful convictions arising from cases within the state. The office had already identified 100 cases, most or all of them involving the possible misapplication of hair microscopy, that would be under review.

Other significant contributors to wrongful convictions uncovered by The Innocence Project involved eyewitness misidentifications (witnesses identified the wrong person as the perpetrator), the use of jailhouse informants, and the use of false confessions.

It’s counterintuitive, Neufeld said, that anyone would confess to a crime that he or she did not commit. But juveniles, individuals with mental disabilities, and people who are simply more compliant, are disproportionately likely to make false confessions during police questioning.

“They think, ‘I’m going to confess and get the heck out of here, and the evidence will set me free,’ and then it doesn’t,” Neufeld said.

In some cases, police or prosecutors engage in misconduct that buries or misstates evidence that would be favorable to the defendant. In other cases, the individuals in the courtroom—from lawyers, to judges, to jurors—are unable to assess the reliability of evidence presented by expert witnesses.

“In the criminal context, there is no FDA, there is no regulatory or scientific body, to [assess the validity of forensic techniques],” Neufeld said. That is supposed to be figured out in the courtroom; and boy, is the courtroom a poor place to do that.”

The afternoon prior to the lecture, Neufeld sat around a table with three Drake University students for a private discussion. He emphasized that dedicated students have the power to create meaningful social change.

“This whole Innocence movement started out as a little clinic at one law school,” Neufeld said. “We had 15 students, that was 23–24 years ago, and it evolved because of the work and the way young people responded to the issues.”

Now the organization has a full-time staff of 85 people, more than 40 affiliated projects around the country, and nearly 20 projects in countries around the world.

Where many prosecutors view a “win” in the courtroom as a conviction for the defendant, Neufeld sees the process differently. Each life freed from improper incarceration represents a victory for Neufeld. And every misapplication of criminal procedure is a sleight to liberty and justice.

“Our Constitution guarantees every person in this country will get a fair trial, and a fair trial means that prosecuting attorneys and witnesses can’t put their thumb on the scales of justice,” Neufeld said during the Bucksbaum Lecture. “When they do that, the integrity of the process is undermined.”

Drake junior Matt Wilkens, a Management major, hopes to become a prosecuting attorney after he graduates. He said he was inspired by his meeting with Neufeld, as proper values and ethics are essential in the legal profession. He said a commitment to ethics has been infused in every course he’s taken so far at Drake.

“In an ideal world,” he said, “a prosecutor and defense attorney would be able to work closer together, with the ultimate goal being to find the truth to the best of their ability with the information available.”