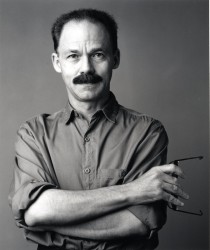

Gaylord Torrence |

Gaylord Torrence, professor emeritus of art at Drake, is featured in a recent Wall Street Journal article about the new permanent display of American Indian art that Torrence has developed at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Mo.

The article is titled “Elevating American Indian Art.”

Torrence joined the Drake faculty in 1969 and retired in 2002, when he was recruited by Nelson-Atkins Director Marc Wilson to become the museum’s founding curator of the Department of American Indian Art.

His mission: to fill gaps in the museum’s collection and to assemble the finest examples of diverse Indian art forms, spanning the entire North American continent and the period from before European contact to the present.

The new permanent exhibit occupies more than 6,000 square feet of completely redesigned galleries in the museum’s original building.

Wall Street Journal reporter Lee Rosenbaum described the exhibit as “one of our most important museum collections of American Indian art.” She also noted that the “inaugural display consists of 205 works from more than 65 tribes, astutely chosen and arrestingly installed.”

Torrence acquired about half the works in the inaugural display through purchases and gifts. He defined his goal in simple but uncompromising language: “To find pieces that rank with the greatest of their kind.”

Ojibwa buffalo-skin coat from Ontario. |

The new exhibit features numerous rare and stunning objects, including

a round Arikara shield from North Dakota, c. 1850, fashioned from

buffalo rawhide and bearing a haunting image of a buffalo bull. The

shield, according to Torrence, is a record of a vision experienced

“after prolonged fasting and prayer by someone seeking a

spirit-helper.”

Another key piece is a rare, elaborately ornamented Ojibwa

buffalo-skin coat from Ontario that is displayed near the entrance.

Boston dealer Ned Jalbert, who contributed the coat, described it as “a

transformational object — something that can change how people think

about an institution by creating a sensation.”

“Museums have never quite settled on how to present Indian objects,” Rosenbaum said in her article.

“Natural history museums tend to treat everything from arrowheads to totem poles as enthographic artifacts. Others, including the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian, regard Indians as their most important constituency and focus on the meaning and importance of objects to their original communities.

“Art museums prize these creations for their beauty, but often treat them as a subset of what used to be called, insensitively, ‘primitive art.'”

Wilson, the veteran director of the Nelson-Atkins Museum, told Rosenbaum that he wanted none of that. He told her that his goal “was to finally do away with the prejudices and stereotypes that color the way people look at American Indian art.”

The Nelson-Atkins Museum is recognized nationally and internationally as one of America’s finest art museums. Admission is free.