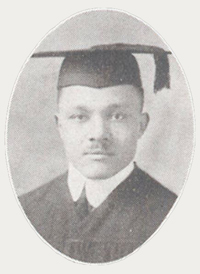

Howard P. Drew, LW 1920, was many things: Olympic athlete, World War I veteran, and ground-breaking African-American judge. In honor of the Drake Relays, in which Drew competed nearly a century ago, Drake Law School is commemorating this outstanding alumnus.

Drew was born June 28, 1890 in Lexington, Va. and raised in Springfield, Mass.

His first track meet was the Springfield City Games in the summer of 1905. With no money to buy spikes, he hammered roofing nails through the soles of his tennis shoes. After winning the 100-yard dash, the nails hurt his feet so much he ran—and won—the 440-yard dash in bare feet.

“I went home with sore feet but very proud of my two medals,” Drew later said.

In high school, he was a star athlete in football, baseball, and track. The 1912 Springfield High School yearbook, The Pnalka, wrote:

“In the 100-yard dash, the 220-yard dash, the 120- and 220-yard hurdles, and running broad jump, Capt. Drew is without a peer… Never before has Springfield had such an athlete, and one can almost say, never again will she be so fortunate.”

Olympic Games

While still in high school, Drew won the 100-meter dash at the U.S. Olympic trials, tying the world record and beating the fastest American of the time, Ralph Craig.

Drew qualified for the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden, where he was not only the gold medal favorite in track, but also the only African-American member of the U.S. exhibition baseball team.

At the Olympics, Drew easily won the 100-meter trial heat. But at the halfway mark during the semi-finals, he struck a piece of soft track and pulled his tendon. He had such a lead that he won by hopping across the finish line.

For the 100-meter finals, Drew went to the starting line but had to be helped off the track. The trainers told him he risked permanent injury, so Drew watched as his teammate Craig won gold. Craig was later inducted into the USA Track and Field Hall of Fame.

Michael J. Murphy, official trainer of the 1912 U.S. Olympic team, later said of Drew: “But for that unfortunate happening I believe he would have proven America’s greatest sprinter since the days of [Bernard] Wefers. I say this without underestimating Craig’s fine running.”

College Years

Drew enrolled at the University of Southern California (USC), where he was a national AAU champion in the 100-meter dash and 200-meter dash. He also set world records in the 100-yard dash and 220-yard dash, as well as the 70-yard sprint and 90-yard sprint.

In 1916, Drew competed in a special invitational event that brought together the world’s best sprinters. Held at Madison Square Garden in New York City, the crowd was the largest-ever for an athletic event in the arena at that time, and the fire department had to close the doors to contain the crowd.

During the event, Drew won the 70-yard sprint, tying his own world record at 7.2 seconds. The New York Times called him “the leader in his class.”

Drew was later referenced in a 1918 Popular Science magazine article, which stated that his 9.6-second record in the 100-yard dash was “the greatest speed attained by any man.” Thus, Drew became the original “World’s Fastest Human,” a title later held by sprinters such as Jesse Owens, Carl Lewis, and Usain Bolt.

Law School and World War I

In the fall of 1916, Drew enrolled at Drake Law School. As a student, he competed in and helped coach the track team and played football. He also served as a motivational speaker.

His legal education was interrupted by World War I. In August 1918, Drew enlisted as a private in the U.S. Army and rose to sergeant, receiving a Victory Medal and defensive bar for his service.

Drew was once again denied his gold-medal dreams when the 1916 Olympic Games were cancelled due to the war.

In the summer of 1919, the Allied Troops held the Inter-Allied Games in Paris. As a star athlete, Drew was featured on promotional materials for the event, and he helped select and train the U.S. track team.

Following the war, Drew returned to finish his law degree at Drake. He continued to participate in football and track, as well as tennis.

An article in The Drake Delphic noted that fans “for two years have been waiting to see Howard Drew matched against the speediest sprinters of the country.” In 1920, he competed in the Drake Relays, winning his heat and placing third in the finals for the 100-yard dash.

Drew also impressed in the classroom. He secured a spot on Drake’s Model Senate team and was noted as “a heady debater with excellent platform presence” in The Drake Delphic.

After graduating from Drake Law School, Drew competed once more in the U.S. trials for the 1920 Olympics. But now in his 30s and plagued by injuries, he did not make the team.

Civil Rights Advocate

Throughout his life, Drew used his fame to fight for equality and civil rights. He once refused to participate in a Boston Athletic Association track meet because the organization had banned African-American athletes.

“As long as the B. A. A. has this rule I shall never appear there,” Drew said at the time. “The club states specifically that it does not want negroes and under the conditions I think it would be foolish for me to appear there as a money-making attraction for them.”

At USC, Drew was the first African-American man to write for the campus newspaper, the Daily Southern Californian. His bylined column focused on civil rights, education, and fitness. He also met the legendary Booker T. Washington on a speaking tour and was featured on the cover of the July 1915 edition of the NAACP’s The Crisis magazine.

After law school, Drew passed the Ohio and Connecticut bars and set up his own law practice in Hartford, Conn. He later became the first African-American judge and justice of the peace in the state and committed his career to civil rights, housing, and unemployment issues.

Drew died in 1957 and is buried in a small veterans cemetery in Windsor, Conn.

He was inducted into the Massachusetts State Track Coaches Association Athlete Hall of Fame in 2012. In 2016, Drew received special recognition by the U.S. Congress and a certification of congratulations from the Massachusetts Senate and House of Representatives.

The certification recognized Drew for “being the ‘fastest man in the world,’ breaking outstanding records, fighting for civil rights, and remaining a symbol of hope.”