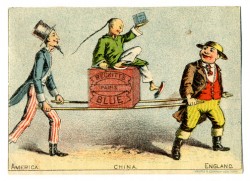

This advertising trade card depicts China being “carried” by the United States and England. |

Exhibit explores portrayal of the Chinese in American 19th Century advertising trade cards

By Emilee Richardson

Drake University’s Anderson Gallery opened the fall season with an exhibition of hundreds of 19th century advertising trade cards that feature images of Chinese people or motifs.

“America Imagines Chinese: 19th Century Advertising Trade Cards and the American Imagination” opened Friday, Sept. 5, and continues through Oct. 17.

Lenore Metrick-Chen, Drake assistant professor of art history, will conduct a gallery walk at 6 p.m. All of the 274 advertising trade cards in the exhibition are from Metrick-Chen’s personal collection.

Trade cards were dominant form of advertising

Advertising trade cards, which measured approximately 2-by-6 inches, were introduced in America in the mid-19th century. By 1876, they circulated widely and were becoming the dominant method of advertising. The trade cards — given away free in stores and on the street — announced every new product and innovation in miniature, full-color pictures.

Metrick-Chen said the chromolithography technique was nicknamed “democratic art” because it allowed everyone to be able to own usually expensive colorful images.

She has been collecting the cards for eight years since becoming interested while researching her Ph.D. dissertation, “Collecting Objects, Excluding People – Chinese Subjects and the American Art Discourse, 1870-1900.”

“At first, I hadn’t thought of using advertising or drawings for my dissertation,” said Metrick-Chen, who earned her Ph.D. in art history at the University of Chicago. “But after some thought, I realized they were very interesting because the U.S. was barring Chinese people from immigrating to the States and at the same time, using them in advertisements.”

Cards proved popular during ban on Chinese immigration

The popularity of the cards occurred during the same period as America’s first Chinese Exclusion Laws banning Chinese immigration. Because of this prohibition, few Americans in the Eastern states had direct contact with Chinese people. Nevertheless, hundreds of trade card images for domestic and international products depicted Chinese figures and the Chinese image that became a familiar — though not altogether positive — icon.

The trade card’s iconography had less to do with the product advertised than its place in the new visual language emerging with America’s transformation from a rural agricultural economy to an urban manufacturing one. Both directly and indirectly, the imagery reflects social and cultural issues arising during this tumultuous period of American modernization.

One card, for example, shows the West “carrying” China — literally on a box of laundry whitener and figuratively within the world economy. “Inequality is implicit in the imagery,” Metrick-Chen said.

The reception and exhibition are free and open to the public. Gallery hours are noon to 4 p.m. Tuesday through Sunday. For more information, contact Heather King at 515-271-1994 or heather.king@drake.edu.